Right from the day in 1940 when Åsmund S. Lærdal founded his company in Stavanger, Norway, he applied his firm basic principles which already then encompassed the concept of stakeholders and teamwork. One major stakeholder was clearly defined: the child. Producing high-quality books and toys for children meant providing joy. During WWII, raw materials could be impossible to find. Under cover of the dark nights he travelled illegally along the fjords to buy wood for toys. He and his team kept developing and improving a richness of new varieties – always with an eye on stimulating the child’s active involvement and imagination.

A rich heritage

Soon after the war, he travelled to the USA to search for new materials and found the basics for soft plastic. After intensive experiments and work to develop pioneering processes and machines, the company rapidly became one of the European leaders in quality dolls and indestructible model cars. The Anne dolls – in ever new but always beautiful versions – were soft and cuddly; the cars were so precisely modelled that collecting them became a dream for boys as far away as Hong Kong.

Tribute to Åsmund S. Laerdal on October 11th, 2013, the 100th anniversary of his birth.

The Tomte toy cars introduced in the mid 1950s were exported to over 50 countries. (Photo from the Norwegian Childhood Museum in Stavanger). About one million Anne dolls were made in the 1950s in a hundred different models. Today they are collectors’ items.

Moving Into Life Saving

When the Laerdal expertise in soft plastics led the Norwegian Civil Defence to ask the company to develop imitation wounds for training, Åsmund persuaded the emergency department of the University Hospital in Oslo to let him install a camera for them to provide the necessary details. Collaboration with an experienced surgeon yielded accurate models of relevant wounds. A detailed and thorough process resulted in Practoplast kits with 33 different wound imitations; this kit was adopted on several continents.

Contacts made through the work with wound imitations alerted Åsmund to the group of physicians and engineers in Baltimore that had developed a new and much more effective method for resuscitation, involving mouth-to-mouth breathing. He was instantly receptive – and in this case, his interest had a strong emotional element as well, after the experience of having found his little son, Tore, lifeless in the water.

The big question was how people could learn this new technique. After testing a prototype face mask on spluttering volunteers, Åsmund soon became convinced that a life-size manikin would have the greatest potential. He appealed to Stavanger’s only anaesthesiologist at the time, Bjørn Lind, for help, and the two worked closely together for a year to make every detail anatomically correct. The name was to be Resusci Anne – drawing a line back to the play dolls and the expertise needed to produce them. Quality was an absolute, but at the same time the price had to be affordable: “It is much more meaningful to make 10,000 manikins at NOK 1,000 each than 1,000 manikins at NOK 10,000,” said Åsmund. He was adamant: “When people choose to exchange their money for a Laerdal product the exchange must benefit both.”

When Åsmund brought the prototype Resusci Anne to the US in 1960 and met the resuscitation pioneers Peter Safar and Archer S. Gordon, the chemistry was instant and Peter and Åsmund became lifelong close friends and collaborators.

The year 1960 also led to ground-breaking research: having become a strong advocate, Bjørn Lind played a key role when manikins were used for the first large-scale training of school children. The outcome was scientifically recorded, analysed and published in the leading Journal of the American Medical Association, JAMA. Norway had shown the way: every school child could learn how to save a life.

Åsmund S. Lærdal practising resuscitation on an early Resusci Anne.

“All school children are to learn the mouth-to-mouth method” – media coverage of the successful pioneer project.

When Åsmund Saved His Son

When the two older siblings, Astrid and Åge, called out to their parents that their little brother had fallen into the water, Åsmund S. Lærdal reacted instinctively. Thanks to the air inside his rain-suit, two-year old Tore was floating but face down, unconscious and icy cold. Having held him upside-down and shaken him to drain out the water and help him breathe, Åsmund ran uphill to bring him into the cottage, stripped himself and Tore, and lay down in the bed cuddling him to warm him up. Åsmund and his wife, Margit, had previously lost their first child, Signe Marie, in a neonatal hospital epidemic. The near drowning of Tore on top of this tragedy was all the more traumatic to them and contributed to Åsmund’s personal and unspoken motivation for what he later devoted his life to.

Bjørn Lind – Stavanger’s resuscitation pioneer

(Video in Norwegian with English subtitles)

(Video in Norwegian with English subtitles)

New Concept: The Trained Bystander

Åsmund S. Lærdal initiated and sponsored the first international symposium on emergency resuscitation in Stavanger a year later. The conclusion was simple and clear: first-aid workers of all categories, school children and the general public should be taught mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, and the training should be compulsory for all school children. Åsmund expressed the way forward: “Implement what has been shown to work, and drive therapy through education.”

At this stage, compressions were considered too risky for lay people to administer, being reserved for professional health carers and certified life savers. But Peter Safar had already suggested a flexible chest ring inside Resusci Anne for compression simulation. In his quiet, almost self-effacing but determinedly efficient way, Åsmund was a persistent key mover. He supported the production and printing in 12 languages of Safar’s CPR manual and enabled Norwegian anaesthesiologists to organise a new international symposium in 1967, which recommended that all health personnel should be trained in the full CPR method. Seven years later the American Heart Association (AHA) decided to recommend that lay people should also train in chest compression; any chest injuries would be outweighed by the chance of preventing lasting brain damage or death.

That same year Åsmund established Laerdal Medical Corporation in Armonk, NY – the first step in creating an international company. In line with this, the Norwegian vowel ‘æ’ in the company name was replaced by the more easily internationally grasped ‘ae’. The family, however, retained the Norwegian spelling of the name.

At the 50th anniversary of modern life saving in 2010, the AHA estimated that about 350 million people around the world had been trained in CPR, most of them on Resusci Anne. CPR was recognized as one of the most important public health initiatives in the last two generations and is now estimated to have contributed to saving at least 2 million lives.

The inventor and industrialist, the father of modern resuscitation, and the specialist who helped develop the manikin and demonstrated that even school children could learn by using her: Åsmund S. Lærdal, Peter Safar and Bjørn Lind.

Never Satisfied with the Status Quo

Åsmund was always seeking to improve things. He kept listening and discussing needs for innovation with his increasing network of users and specialists. Resusci Anne gained a family: Resusci Andy and Resusci Baby, and, two decades later, Resusci Junior. Resusci Anne herself acquired innovative, performance-recording features to address the AHA’s desire for trainees to “Practice to Perfection”. As other urgent needs became clear to Åsmund, he responded with the Resusci Folding Bag – the predecessor to the world-leading Silicone Resuscitator launched in the 1980s.

Girl from the River Seine

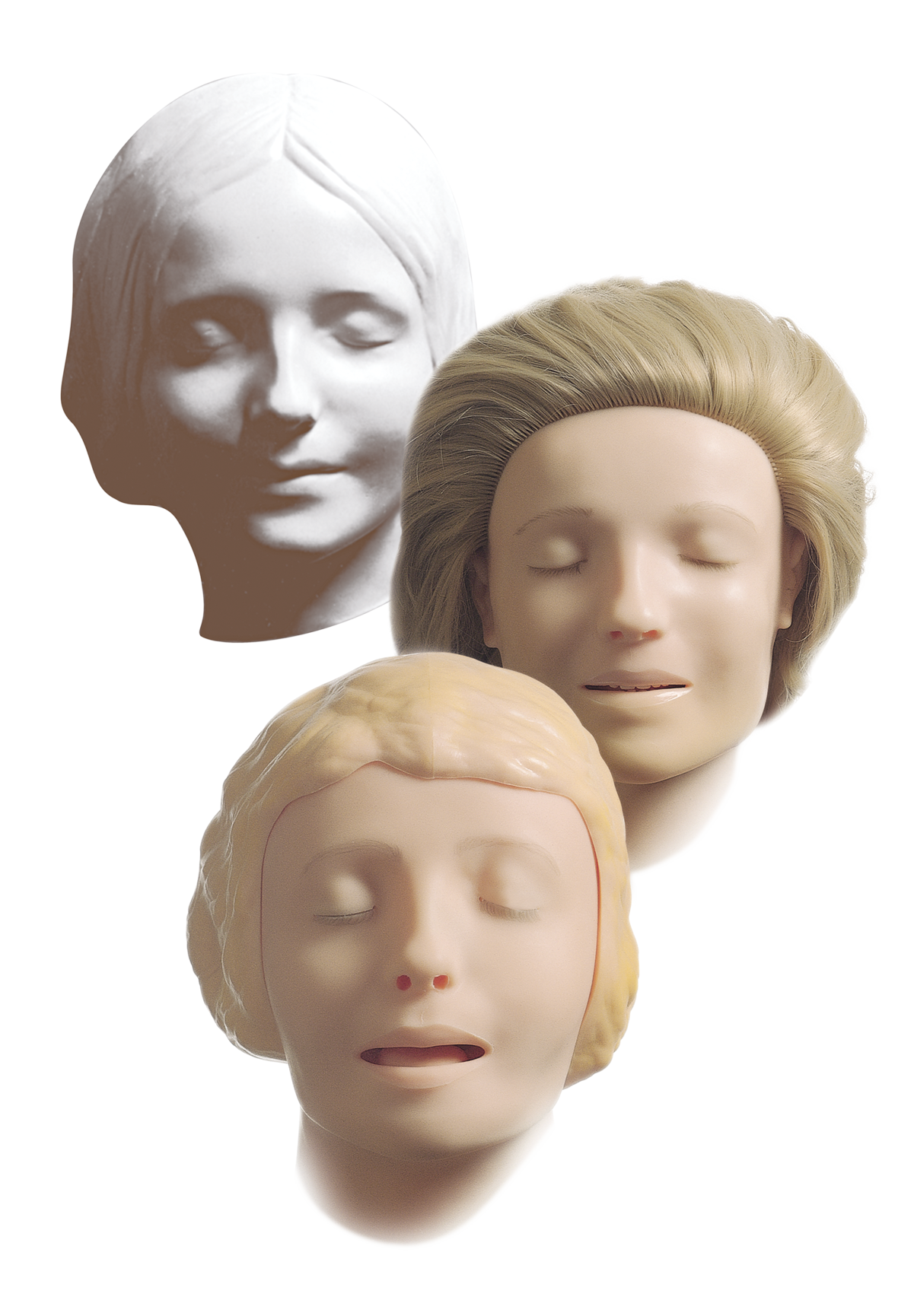

In the 1950s, a person who did not breathe was considered dead. One important question was the face of the manikin: ”How could it appear dead and yet not be too scary to breathe into?” Åsmund always immersed himself in a problem, thinking and discussing with his nearest collaborators and thinking again. In this case he found the answer in a face mask in the home of his parents-in-law. In the late 1800s, a Paris modeller of death masks had been so struck by the serene expression of a beautiful young woman who was found drowned in the River Seine that he made a cast for what was to become a bestseller: the enigmatic “L’Inconnue”, the unknown.

Åsmund commissioned the Danish sculptor, Emma Mathiassen, who had shaped the face of the Anne dolls, to create a face for Resusci Anne based on this mask. In this way, “L’Inconnue” has played her part in helping save millions of lives around the world and continues to help convince learners that they are able and willing to act when a life is at stake. The face of death became the face of life.

The Vision of Helping Low-Income Countries

Even before starting his own company, Åsmund S. Lærdal had told his wife-to-be, Margit, of his dream to make so much money that he could afford to give away half. All along, he had provided direct financial support to the mission of helping saving lives, mostly behind the scenes. In 1980, he finalised his plans for the Laerdal Foundation for Acute Medicine and provided it with a starting capital of NOK 10 million ($1.1m). Over the years, this foundation has supported close to 2,000 research projects, in recent years with annual grants totalling up to NOK 40 million.

Also, Åsmund thought about handing over the company – his son Tore had joined Laerdal in 1975 after graduating – and devoting his own energies to help low-income countries, in the sense of helping people to help themselves. As he expressed it: “Equipping the people not with tractors but with better spades.”

However, Åsmund S. Lærdal became seriously ill and died in November 1981 before the Foundation’s first award ceremony. Tore was not yet 30, but with the mission in his blood he shouldered the full responsibility for running the company. 30 years later, he realised his father’s vision by establishing Laerdal Global Health.

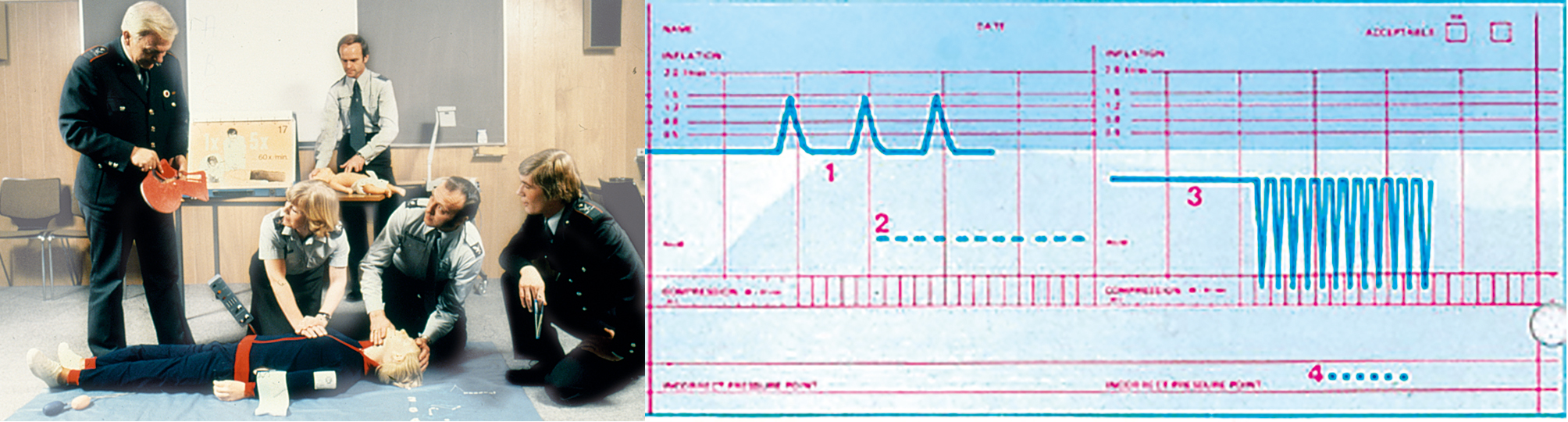

The Recording Resusci Anne provided feedback, printing out an accurate recording of ventilation and compression quality.

Promoting Mass Training

In 1982, the Laerdal Foundation helped initiate and support an international conference for CPR trainers in London, where the AHA presented their support programs for basic and advanced life support. This example from the US stimulated health authorities, schools, rescue organisations and Laerdal to collaborate on projects for mass CPR training in the Stavanger region of Norway.

These demonstrated that a two-hour course sufficed to train trainers, and successful training of 5,000 lay persons over just two weekends pointed to great potential.

Inspired by these experiences, Stig Holmberg in Gothenburg developed a Swedish CPR training model, primarily aimed at healthcare personnel. Laerdal contributed with a training program and sponsored thousands of large posters for hospitals and health institutions: complex algorithms were given a simple-to-grasp expression, making them easy to learn. These posters proved so popular that special editions were added, for rescuing children and infants. Over the years, posters in many languages were printed for the European Resuscitation Council for displaying in thousands of hospital emergency rooms and training sites. In addition, pocket-size versions were supplied for use as personal reminders.

Peter Safar

“The father of modern resuscitation”

Video on the history of CPR featuring Peter Safar

Heartstart Defibrillator

Moving into Hi-Tech

By the mid-80s Laerdal’s internationalisation had progressed rapidly. Whereas the number of employees in Stavanger remained at about 350, sales companies in eight countries had increased the total employed to about 600. US experiences drew Laerdal’s attention to the value of early defibrillation as well as CPR to improve survival from cardiac arrest.

This spurred a move into hi-tech. For the first time Laerdal decided on a joint venture with another commercial company, First Medic in Seattle, resulting in Heartstart 2000 – the first generation “intelligent” machine for the crucial shocking needed to restart an arrested heart. Such machines are called automated external defibrillators (AEDs). Till then, defibrillation had only been practical in hospital settings and in a small number of emergency services with highly trained personnel; now the goal became for all EMS personnel to start CPR within four minutes of the out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and defibrillate within eight minutes. The use of AEDs facilitated this because they required less training to use. Also, importantly, Heartstart 2000 logged vital data allowing for medical quality assurance, overcoming reservations from some quarters about EMS personnel defibrillating patients. Upgrades to Heartstart 2000 followed and a few years later led to an alliance with Hewlett Packard (subsequently Philips Medical) and further innovations in early defibrillation. This alliance lasted over 20 years – extraordinary for corporate alliances.

Another long-standing alliance, the one with the AHA, led to Laerdal’s purchase of Actronics, a company leasing an AHA-owned patent. Actronics was pioneering the use of computers for training and needed venture capital; this led to the development of the HeartSim cardiac rhythm simulator, a precursor to the e-learning suite of products in use today.

Team training with equipment including HeartStart MRx and the Laerdal Silicone Resuscitator.

Recognising Errors – and Learning from Them

In the ‘90s, John Schaefer and René Gonzalez in Pittsburgh tinkered to equip an extremely costly and rare simulator – which was reserved for research only – with crucial airway functions. Medical Plastics Laboratory (MPL) in Texas acquired exclusive rights to use their subsequent patent in its manikins, at a time when MPL and Laerdal were discussing a joint venture to update Resusci Anne. Laerdal acquired MPL around 2000 – the year after the Institute of Medicine in the US had presented its landmark report “To Err is Human”, estimating that up to 100,000 lives were lost every year due to medical errors in the US alone. The report listed its arguments for patient simulation training: optimally efficient learning method; realistic preparation for rare, difficult cases; and allowing errors to be made without harm to patients, analysing them, and repeating the team’s efforts in order to improve.

This triggered the development of SimMan by combining MPL’s airway torso trainer with the Laerdal HeartSim rhythm simulator. The result cost a fraction of previous simulators and was eminently suited for both training and research, causing a true disruption – a revolution not only in the training itself, but in the culture by admitting errors, making it natural and positive to discuss them in constructive ways and improve procedure, and working to avoid errors. It was an instant hit: simulation centres were set up on several continents based around SimMan.

Over the years, constant collaboration on further developments yielded a range of programs and products, among them the Nursing Anne Simulator. Both the scope of the nursing role and the requirements for training nurses and nursing students have changed dramatically. Practising core skills with the different modules of Nursing Anne enhances clinical knowledge, allows trainees to experience highly realistic patient encounters and in these ways prepare them for the highest level of care.

The first SimMan, launched in 2002.

13-year old Hanne Haug, in Våland School, Stavanger, training to become a life saver.

The Contrast: Low-Tech Mini Anne

At the same time as this hi-tech revolution had begun, the AHA challenged Laerdal to collaborate in developing a dramatically simplified and low-cost, video-based CPR program for lay people that could be delivered in 30 minutes – well within the time of a school class – compared with two to four hours for traditional courses. 30 years after the CPR pioneers had prepared the ground for mass training, the number of bystanders ready and willing to act immediately was still far too low in many communities. The materials for complete and efficient hands-on training should cost less than $30.

The result was the Mini Anne kit which was proven to be a very effective training tool in extensive evaluations. It was launched by the AHA in New York in 2005 under the name CPR Anytime. In Denmark, Trygfonden, the Tryg Foundation, collaborated with the Danish Resuscitation Council and Red Cross to offer a Mini Anne kit to every 13-year old. Training the young, who will live the longest, is vital. Letting them keep the kit meant that they could convey their proud new skills especially to more elderly family members – the ones who are most likely to be faced with a cardiac arrest in their homes.

A New Opening: Laerdal Global Health

In 2006, the Norwegian anaesthetist, Mads Gilbert, drew Tore Lærdal’s attention to the area which now accounts for the largest share of the Million Lives goal: maternal and newborn deaths. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) believed that the key was educational methodology that increased both competence and confidence, and they partnered with Laerdal to help advance educational science and resources needed for training in neonatal resuscitation.

The AAP had created the Neonatal Resuscitation Program course for the US, and this had been rolled out to 120 mainly high-income countries (HICs). However, this program was too complex and resource demanding to be used widely in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), and increased attention at the time on the UN Millennium Development Goal 4 made clear that a new approach was needed. A Laerdal team collaborated with the AAP to develop the NeoNatalie simulator and helped draft the educational materials. The Helping Babies Breathe program was on its way. This led to contacts with Jhpiego, an NGO based in Baltimore, US, whose focus was on the well-being of the mothers.

But the enormous scale of the task ahead, to reduce newborn and maternal mortality, called for a wider network of partners and alliances. To facilitate this, in 2010 Tore Lærdal established the not-for-profit company, Laerdal Global Health (LGH). Turning his full attention to this new venture he became the leader of a small entrepreneurial team. The global health alliances and programs that followed are described in a later chapter.

A key element of all these programs was Laerdal’s highly respected expertise in visual expression. Right from the beginning, Åsmund S. Laerdal had stressed the importance of visual clarity and attractiveness by commissioning leading artists to design his children’s books and his dolls. This emphasis remains a key element, leading to specialists in education working ceaselessly to reduce visual programs to the essential and instantly graspable, while ensuring that any anatomical details are correct. As a result, training programs including the LGH ones are easily adjusted to overcome language differences and even shortcomings in literacy.